Update 2022-10-26: WWALS response to opposition comments by Eagle LNG about small, inland LNG 2022-10-17.

Update 2022-10-04: WWALS response to FERC on opposition comments of Pivotal LNG about small, inland LNG Rulemaking 2022-10-04.

Update 2022-07-23: FERC requests comments on WWALS Petition for Rulemaking on FERC Oversight of Small-Scale Inland LNG Export Facilities 2022-07-22.

FERC has filed our petition in a new docket, RM22-21. We shall see what they do from there on this request to open a Rulemaking to revisit, as FERC Chair Richard Glick has suggested, FERC’s decisions of 2014 and 2015 that left small inland LNG export facilities without environmental oversight.

Many thanks to Cecile Scofield for keeping after this issue for years, and to the rest of the WWALS Issues Committee.

And thanks to each of our co-signers, each of whom makes this request much stronger: Earl L. Hatley, President, LEAD Agency, Inc.; Dr. John C. Capece, Executive Director and Waterkeeper, Kissimmee Waterkeeper®; Terry Phelan, Interim President, Our Santa Fe River, Inc.; David Kyler, Director, Center for a Sustainable Coast; Heather Hulton VanTassel, Executive Director, Three Rivers WATERKEEPER®; and Jefferson Currie II, Lumber Riverkeeper®, Winyah Rivers Alliance.

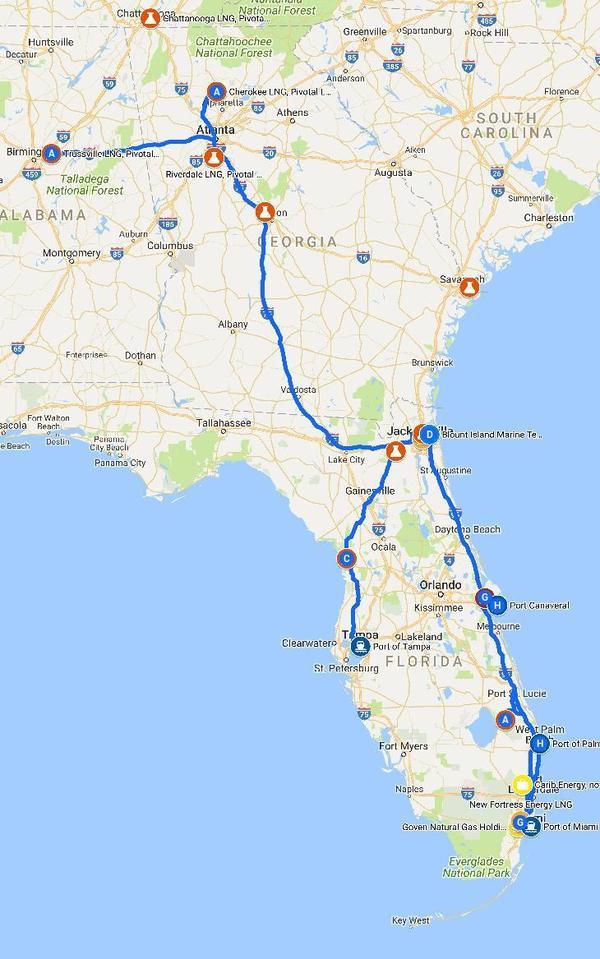

Our map needs to be expanded to add inland LNG operations in Pennsylvania and North Carolina, which are mentioned in this petition.

Map: by WWALS, from federal and state filings of LNG export operations.

Below are the cover letter and the petition.

The Cover Letter

See also PDF.

July 19, 2022

To: Honorable Kimberly D. Bose, Secretary

kimberly.bose@ferc.gov

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

888 First Street, N.E.

Washington, DC 20426

Chairman Richard Glick

richard.glick@ferc.gov

OPP@ferc.gov

Cc: Ms. Tina Ham

tina.ham@ferc.gov

Ms. Anne Marie Hirschberger

Office of the General Counsel

Sarah McKinley,

Office of External Affairs

sarah.mckinley@ferc.gov

Thach D Nguyen (PHMSA)

thach.d.nguyen@dot.gov

Re: Rule 207(a)(4) Petition for Rulemaking for Small-Scale Inland LNG Export Facilities in FERC Docket No RM22-__-000

Dear Secretary Bose:

Enclosed is the Petition of WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc., LEAD Agency, Inc., Kissimmee Waterkeeper, Our Santa Fe River, Center for a Sustainable Coast, Three Rivers Waterkeeper, and Lumber Riverkeeper, for Rulemaking on FERC oversight of LNG Export facilities. As detailed therein, the Petitioners respectfully request that the Commission issue a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NOPR”) to ensure that the Commission is carrying out its statutory responsibilities under the letter of the law, specifically the Commission’s jurisdiction under section 3 of the Natural Gas Act (“NGA”), by revisiting and reconsidering Commission decisions that a Liquid Natural Gas (“LNG”) facility must be connected to a pipeline to qualify as an LNG terminal, or that such a facility must be located where ocean-going ships directly load LNG for export to be considered an LNG export facility.

If there are any questions, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Respectfully submitted,

John S. Quarterman, Suwannee RIVERKEEPER®

/s

WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc.

Earl L. Hatley, President

/s

LEAD Agency, Inc. (Grand Riverkeeper®, Tar Creekkeeper®)

John C. Capece, Ph.D., Executive Director and Waterkeeper

/s

Kissimmee Waterkeeper®

Terry Phelan, Interim President

/s

Our Santa Fe River, Inc.

David Kyler, Director

/s

Center for a Sustainable Coast

Heather Hulton VanTassel, Executive Director

/s

Three Rivers WATERKEEPER®

Jefferson Currie II, Lumber Riverkeeper®

/s

Winyah Rivers Alliance

The Petition

See also PDF.

Filed by FERC as Accession Number 20220722-5043, Petition for Rulemaking of Small Scale Inland LNG Export Facilities of WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc., et al. under RM22-21.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BEFORE THE

FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION

|

Petition For Rulemaking of WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc., LEAD Agency, Inc., Kissimmee Waterkeeper, Our Santa Fe River, Center for a Sustainable Coast, Three Rivers Waterkeeper, and Lumber Riverkeeper |

) ) |

RM22-__-000 |

PETITION FOR RULEMAKING ON FERC OVERSIGHT

OF SMALL-SCALE INLAND LNG EXPORT FACILITIES

BY WWALS WATERSHED COALITION, INC., LEAD Agency, Inc., Kissimee Waterkeeper, Our Santa Fe River, Center for a Sustainable Coast, Three Rivers Waterkeeper, and Lumber Riverkeeper

John S. Quarterman, Suwannee RIVERKEEPER®

/s

WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc.

Earl L. Hatley, President

/s

LEAD Agency, Inc.

Dr. John C. Capece, Executive Director and Waterkeeper

/s

Kissimmee Waterkeeper®

Terry Phelan, Interim President

/s

Our Santa Fe River, Inc.

David Kyler, Director

/s

Center for a Sustainable Coast

Heather Hulton VanTassel, Executive Director

/s

Three Rivers WATERKEEPER®

Jefferson Currie II, Lumber Riverkeeper®

/s

Winyah Rivers Alliance

July 19 , 2022

TABLE OF CONTENTS

A. FERC did not follow legislative intent 7

i. Shell U.S. Gas & Power, LLC (“Shell”), 148 FERC ¶ 61,163 (Sept. 4, 2014), Docket No. RP14-52-000 7

ii. Emera CNG, LLC (“Emera”), 148 FERC ¶ 61,219 (Sept. 19, 2014), Docket No. CP14-114-000 8

iii. Pivotal LNG, Inc. (“Pivotal” or “Pivotal II”), 151 FERC ¶ 61,006 (Apr. 2, 2015), Docket No. RP15-259-000 9

B. Analysis of how FERC failed to follow the law 10

C. Some consequences of FERC’s failure to follow the law 11

i. Pennsylvania and New Jersey 11

iii. Florida inland LNG facilities 12

1. New Fortress Energy, Miami, Florida 13

2. New Fortress Energy, Titusville, FL 13

3. Strom, Inc., Crystal River, Florida 14

D. Importance of methane as a greenhouse gas acknowledged by courts and FERC 15

E. Method of reconsideration 18

WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc. (“WWALS”) 19

Kissimmee Waterkeeper (“Kissimmee”) 20

Our Santa Fe River (“OSFR”) 21

Center for a Sustainable Coast 21

A. What FERC’s Strategic Plan and the NGA say FERC should do 23

B. Time to reconsider and revisit 24

C. Summary: safety, environmental, and economic consequences 25

A. Revoke previous decisions and take back up oversight of inland LNG export facilities; or 26

B. Mandate Petitions for Declaratory Order; or 26

C. Send ORDERS to SHOW CAUSE to each inland LNG export facility 26

Shell: Norman Bay Dissent, 148 FERC ¶ 61,163 (Sept. 4, 2014), Docket No. RP14-52-000 28

Emera: Norman Bay Dissent, 148 FERC ¶ 61,219 (Sept. 19, 2014), Docket No. CP14-114-000 29

Pivotal: Norman Bay Dissent, 151 FERC ¶ 61,006 (Apr. 2, 2015), Docket No. RP15-259-000 31

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BEFORE THE

FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION

|

Petition For Rulemaking of WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc., LEAD Agency, Inc., Kissimmee Waterkeeper, Our Santa Fe River, Center for a Sustainable Coast, Three Rivers Waterkeeper, and Lumber Riverkeeper |

) ) |

RM22-__-000 |

PETITION FOR RULEMAKING ON FERC OVERSIGHT

OF SMALL-SCALE INLAND LNG EXPORT FACILITIES

BY WWALS WATERSHED COALITION, INC., LEAD Agency, Inc., Kissimee Waterkeeper, Our Santa Fe River, Center for a Sustainable Coast, Three Rivers Waterkeeper, and Lumber Riverkeeper

Pursuant to Rule 207(a)(4) of the Rules of Practice and Procedure of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (“FERC” or “Commission”), 18 C.F.R. § 385.207(a)(4) (2017) and section 553 of the Administrative Procedure Act, WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc. (“WWALS”) submits this Petition for Rulemaking (“Petition”), and respectfully request that the Commission issue a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (“NOPR”) to ensure that the Commission is carrying out its statutory responsibilities under the letter of the law, specifically the Commission’s jurisdiction under section 3 of the Natural Gas Act (“NGA”), by revisiting and reconsidering Commission decisions that a Liquified Natural Gas (“LNG”) facility must be connected to a pipeline to qualify as an LNG terminal, or that such a facility must be located where ocean-going ships directly load LNG for export to be considered an LNG export facility, and instituting a regulatory clarification and certification policy (see Section VI below).

I. INTRODUCTION

Since the Commission disclaimed jurisdiction over inland LNG export facilities [1] (see also Section III.A. below), developers and operators are “self-determining” federal jurisdiction. Residents of densely populated neighborhoods where inland LNG export plants are being sited, constructed, and operated are in harm’s way. FERC has relegated the responsibility to citizens to police potential threats to public health, safety and welfare posed by these high-risk LNG operations. There are no official FERC Dockets that provide the public an opportunity to participate in any approval process for inland LNG plants designed to ship gas to a port or export facility .

FERC has a statutory obligation to minimize risks to the public and environment from FERC-jurisdictional energy infrastructure. Siting, construction, and operation of LNG facilities is governed by a comprehensive scheme of federal regulations. As the “lead” agency, FERC works with other federal, state and local agencies, as well as the general public, to ensure that all public interest considerations are carefully studied before an LNG facility is approved. FERC’s authority under Section 3 includes authority to apply terms and conditions as necessary and appropriate to ensure proposed siting and construction is in the public interest. FERC typically will not authorize an LNG facility if there are continued questions about safety, while citizens are forced to file FOIA requests in a futile attempt to obtain critical information for non-FERC-jurisdictional LNG export plants.

FERC staff provides guidance on addressing siting requirements by the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT). As a cooperating agency , DOT inspects and enforces compliance through a broad range of administration and judicial actions. Prior to filing of an LNG-related application, FERC staff meets, if asked, with the applicant to review conceptual facility design and provide guidance on resolving environmental, safety and design issues.

To fulfill National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 requirements, FERC staff prepares an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), involving much interaction with intervenors, other interested parties, and the public. This step is vital in that it provides the Commission with vital information to make a final determination whether this project is truly in the public interest when considering all variables.

While non-FERC jurisdictional inland LNG production, storage, and transport facilities must comply with the same federal laws as FERC-jurisdictional facilities, there is no “lead” federal agency. There are no Memorandums of Understanding or Interagency Agreements with any cooperating federal, state or local agencies to ensure compliance with the Federal Safety Standards for LNG Facilities, especially including CFR Title 49, Subpart B, Part 193, and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). There is no transparency or public involvement in the siting, construction, and operation of small-scale inland LNG export facilities. As such, the aforementioned signatories request FERC move to institute a rulemaking to clarify which facilities designed to facilitate the export of LNG are under FERC’s jurisdiction under the NGA.

II. COMMUNICATIONS

All communications and correspondence regarding this Petition should be addressed to the following:

John S. Quarterman, Suwannee RIVERKEEPER®

/s

WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc.

PO Box 88, Hahira, GA 31632

850-290-2350

wwalswatershed@gmail.com

www.wwals.net

Earl L. Hatley, President

/s

LEAD Agency, Inc. (Grand Riverkeeper®, Tar Creekkeeper®)

PO Box 146, Quechee, VT 05059

earlhatley77@gmail.com

www.leadagency.org

Dr. John C. Capece, Kissimmee Waterkeeper®

/s

863-354-0554

capece@kissimmeewaterkeeper.org

kissimmeewaterkeeper.org/

Terry Phelan, Interim President

/s

Our Santa Fe River, Inc.

306-243-0322

terry.phelan@oursantaferiver.org

oursantaferiver.org

David Kyler, Director

/s

Center for a Sustainable Coast

221 Mallery Street

St. Simons Island, GA 31522

912.689.4471

Heather Hulton VanTassel, Executive Director

/s

Three Rivers WATERKEEPER®

PO Box 97062, Pittsburgh, PA 15229

Heather@ThreeRiversWaterkeeper.org

https://www.threeriverswaterkeeper.org/

Jefferson Currie II, Lumber Riverkeeper

/s

Winyah Rivers Alliance

252-419-2565

300 Allied Drive

PO Box 554

Conway, SC 29526

III. BACKGROUND

A. FERC did not follow legislative intent

An Act of Congress is a statute enacted by the United States Congress. It can either be a Public Law, relating to the general public, or a Private Law, relating to specific institutions or individuals. Congress ensures agencies follow legislative intent , and agencies are not allowed to make arbitrary decisions. [2] An agency must “articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action.” An agency’s interpretation is not owed deference if “there is reason to suspect that the interpretation does not reflect the agency’s fair and considered judgment on the matter in question.”

FERC failed to provide a reasoned explanation in disclaiming jurisdiction over small-scale inland LNG export facilities. FERC did this in Orders responding to three Petitions for Declaratory Order: Shell, Emera, and Pivotal . Each of the three petitioners requested that FERC disclaim jurisdiction over their operations involving importing or exporting natural gas. Commissioner Norman Bay filed Dissenting Opinions in each of these three cases, which are included in each of the cited orders, and which we have also included in the Attachments of this Petition. In the brief quotations below from these Orders we have added some emphasis in red .

i. Shell U.S. Gas & Power, LLC (“ Shell ”), 148 FERC ¶ 61,163 (Sept. 4, 2014) , Docket No. RP14-52-000

- On October 16, 2013, Shell U.S. Gas & Power, LLC (Shell) filed a petition in Docket No. RP14-52-000. 1 Shell requests the Commission declare that, by virtue of the exemption in section 1(d) of the Natural Gas Act (NGA) 2 for the transportation and sale of natural gas that will be used as vehicular fuel, Shell will not be subject to any provisions of the NGA as a result of its importing liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Canada, liquefying domestic gas, and transporting Canadian and domestic LNG by truck, train, and waterborne vessel between states for the purpose of selling the LNG for use as fuel for vehicles, with any excess LNG being sold as fuel for non-vehicular uses.

- We find herein, for reasons that do not rely on the exemption provided by NGA section 1(d) for vehicular gas, that Shell will not need to apply to the Commission for authorization under NGA section 3 or section 7 for any of its planned facilities and activities.

1 Shell’s Petition for a Declaratory Order ( Petition ) was submitted pursuant to Rule 207 of the Commission’s Rules of Practice and Procedure, 18 C.F.R. § 385.207 (2014).

2 15 U.S.C. § 717, et seq . (2012).

ii. Emera CNG, LLC (“Emera”), 148 FERC ¶ 61,219 (Sept. 19, 2014) , Docket No. CP14-114-000

- On March 20, 2014, Emera CNG, LLC (Emera) filed a petition requesting that the Commission declare that Emera’s construction and operation of facilities to produce compressed natural gas (CNG) that will be transported by trucks to ships for export to the Commonwealth of the Bahamas will not be subject to the Commission’s jurisdiction under the Natural Gas Act (NGA). 2

1 Emera’s Petition for a Declaratory Order ( Petition ) was submitted pursuant to Rule 207 of the Commission’s Rules of Practice and Procedure, 18 C.F.R. § 385.207 (2014).

2 15 U.S.C. § 717, et seq . (2012).

- For the reasons discussed herein, we grant the petition for a declaratory finding that Emera’s proposed facilities and operations will not be subject to the Commission’s jurisdiction under the NGA.

In III. Response , A. NGA Section 3 Authority over Emera’s Facility:

10. While the stated purpose of Emera’s CNG facility will be to compress gas so that it can be exported in ISO containers , the facility will be subject to our section 3 jurisdiction only if we find it will be an “export facility.” Floridian argues that Emera’s facility will constitute a jurisdictional natural gas export facility, and thus, its siting, construction, and operation are subject to the Commission’s jurisdiction.

iii. Pivotal LNG, Inc. (“Pivotal” or “Pivotal II”), 151 FERC ¶ 61,006 (Apr. 2, 2015), Docket No. RP15-259-000

- On December 10, 2014, Pivotal LNG, Inc. (Pivotal) filed a petition 1 requesting the Commission declare that liquefaction facilities operated by Pivotal and its affiliates that produce liquefied natural gas (LNG) that would ultimately be exported to foreign nations by a third party would not be subject to the Commission’s jurisdiction pursuant to section 3 of the Natural Gas Act (NGA). For the reasons discussed herein, we find that the activities described in Pivotal’s petition will not subject the liquefaction facilities to the Commission’s NGA section 3 jurisdiction.

1 Pivotal’s Petition for a Declaratory Order ( Petition ) was submitted pursuant to Rule 207 of the Commission’s Rules of Practice and Procedure, 18 C.F.R. § 385.207 (2014).

4. Pivotal now seeks a declaratory order finding that the LNG facilities it identifies would not be deemed “LNG Terminals” subject to the Commission’s NGA section 3 jurisdiction when engaging in transactions which ultimately result in any of the LNG they produce being exported. Specifically, Pivotal expects it or its affiliates to sell LNG that is (1) produced at the identified inland LNG facilities or supplied by a third party; (2) transported by Pivotal, an affiliate, or third party in interstate and intrastate commerce by means other than interstate pipeline; and (3) subsequently exported, or resold for ultimate export, by a third party.

5. Pivotal asserts that none of the named LNG facilities constitute an “LNG Terminal” as defined by NGA section 2(11), since they are all located inland, unlike the border-crossing pipelines and coastal LNG terminals that the Commission has traditionally regulated under NGA section 3. Pivotal further avers that there is no regulatory gap or public policy rationale that would justify exercise of the Commission’s NGA section 3 jurisdiction.

B. Analysis of how FERC failed to follow the law

Under the Natural Gas Act (NGA), the intent of Congress to regulate the importation and exportation of natural gas was not ambiguous. See 15 U.S. Code 717b(a): “[N]o person shall export any natural gas from the United States to a foreign country or import any natural gas from a foreign country without first having secured an order of the Commission authorizing it to do so.” There is no exception for whether the natural gas is to be used as vehicular fuel ( Shell) , nor compressed or not ( Emera ), nor liquid or not ( Pivotal ), nor how far the facility is from the ocean. The Commission frustrated the intent of Congress i n considering the manner in which Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) was transported to ocean-going carriers for export in Emera, and compounded that frustration in Pivotal .

Section 3 of the Natural Gas Act gave jurisdictional authority over siting, construction, operation and maintenance of onshore and near-shore LNG import or export facilities to FERC. Quoting former Commissioner Norman Bay’s Dissenting Opinion in Emera , the Commission’s jurisdiction under the NGA “should not turn on a 440-yard truck journey.”

In disclaiming jurisdiction over small-scale LNG export facilities, the majority failed to address the plain language of the NGA and, especially in Pivotal, has conflated Section 3(e) of the NGA, which relates to “LNG Terminals” and Section 7, which covers “transportation facilities.”

Nothing in Section 3 conditions Commission’s jurisdiction upon existence of a pipeline running to the port of export. FERC has substituted its policy judgment for that of Congress and has undermined national uniformity with respect to the import or export of natural gas.

Section 1(a) declares “[f]ederal regulation” of “transportation of natural gas and the sale thereof in interstate and foreign commerce is necessary in the public interest.” Section 1(b) provides that the Act “shall” apply to “the importation or exportation of natural gas in foreign commerce and to persons engaged in such importation or exportation.”

Whether pumped into a tanker ship or pumped into an ISO or other container that is transported by truck and/or rail to the dock, natural gas is still being exported. Narrowing the definition of “LNG Terminal” does not change that fact.

C. Some consequences of FERC’s failure to follow the law

By misreading and conflating Section 3(e) of the Natural Gas Act that relates to ”LNG Terminals” with Section 7 that covers “transportation facilities,” FERC has created its own exemption, with these consequences among others:

- FERC has substituted its policy judgment for that of Congress.

- FERC has undermined national uniformity with respect to the import or export of gas.

- When Congress has spoken, it is not for FERC to call a congressional directive “over expansive.”

- FERC has created a significant and unnecessary gap in FERC’s jurisdiction that has left the public and the environment in harm’s way.

- Rail is becoming a virtual rolling natural gas pipeline on wheels for the distribution of LNG from non-FERC-jurisdictional inland LNG production facilities.

Well-known examples of the problem include the New Fortress Energy in Wyalusing Township, Pennsylvania, inland LNG facility with a special permit from the U.S. Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Agency (PHMSA) [3] to ship LNG 200 miles by rail or truck to an LNG export terminal in Gibbstown, New Jersey.

Exacerbating the problem, the U. S. Department of Energy (“DoE”) Office of Fossil Energy (“FE”) is authorizing LNG exports from facilities where federal jurisdiction is unknown and where there are unanswered questions concerning compliance with the Federal Safety Standards for LNG Facilities and NEPA, including multiple facilities in Florida.

i. Pennsylvania and New Jersey

The situation is adequately summarized in a Protest and Motion to Intervene by Sierra Club and PennFuture: [4]

On September 18, 2020, Bradford County Real Estate Partners LLC (“Bradford”) filed a Petition for a Declaratory Order seeking an order by FERC that it did not have jurisdiction to regulate Bradford’s natural gas liquefaction and truck and rail loading facility in Wyalusing Township, Pennsylvania (“Wyalusing LNG facility”) under either Section 3 or Section 7 of the Natural Gas Act (“NGA”). FERC created a docket for that petition labeled CP20-524.

Sierra Club and Citizens for Pennsylvania’s Future (“PennFuture”) hereby move to intervene in this docket and protest this proposed declaratory order. “Intervenors and their members will be harmed by construction and operation of the Wyalusing LNG liquification facility and associated transport of LNG from that facility to Delaware River Partners, LLC’s (“DRP”) Gibbstown Logistics Center (“DRP Gibbstown facility”). We ask for FERC to first consolidate this petition with a similar petition filed by DRP arguing its Gibbstown facility is not subject to FERC jurisdiction. Second, we ask FERC to issue a declaratory order that the Wyalusing LNG facility is within FERC’s jurisdiction under both Section 3 and Section 7 of the NGA. The Wyalusing LNG facility is a “LNG terminal” subject to FERC’s jurisdiction under Section 3 of the NGA, and it is transporting gas in interstate commerce as well as exporting gas in foreign commerce and so is subject to FERC’s jurisdiction under Section 7 of the NGA. FERC precedent does not argue otherwise, and if FERC were not to exercise jurisdiction it would create a regulatory loophole. Movants argue these points in detail in our protest petition, and we hereby incorporate all aspects of our protest petition into our motion to intervene.

ii. North Carolina

With the planned Atlantic Coast Pipeline canceled, Piedmont Natural Gas, a wholly owned subsidiary of Duke Energy, constructed the Robeson LNG liquefaction facility (Robeson LNG) and four-mile supply pipeline without any FERC oversight and minimal state oversight. [5] Built in Wakulla, Robeson County, NC, the facility is located in a high poverty area with a population that is 85% American Indian. With associated pipelines to funnel gas back and forth to the plant, Robeson LNG is impacting wetlands that are crucial to preventing future flooding in the Lumber River Watershed. Further this inland LNG, with its ability to clean, store and transfer gas by truck, creates harmful impacts from leaks of methane, other gasses and filtered pollutants into the watershed and atmosphere. This pollution stream has negative effects on the health and life of our streams, climate and the communities that call this area home.

iii. Florida inland LNG facilities

LNG is not regulated in the state of Florida. There are no state or local agencies that approve the siting, construction, operation and maintenance of inland LNG export facilities that are operating or that have been proposed for development in densely populated communities in Florida. Unaware that FERC has disclaimed jurisdiction over inland LNG export facilities, local agencies punt citizen questions and concerns to the Commission. FERC has created a regulatory gap. It is time for FERC to fix that gap by revoking its 2014 and 2015 Orders that caused the gap.

A brief list of Florida facilities is included in FERC Accession Number 20210817-4000 , “Comments of WWALS Watershed Coalition re NFE Miami LNG under CP20-466,” and we incorporate that list below, with some updates.

1. New Fortress Energy, Miami, Florida

6800 NW 72nd Street, Miami, Florida. See FERC FOIA FY21-04. Also known as American LNG Marketing LLC, LNG Holdings. Approved by DOE for LNG export, DOE/FE ORDER NO. 3690 AUGUST 7, 2015, FE DOCKET NO. 14-209-LNG. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2015/08/f25/ord3690.pdf Facility is producing 100,000 gallons/day of LNG and storing 270,000 gallons onsite. https://www.energy.gov/fe/american-lng-hialeah-facility-terminal First containerized LNG export occurred on February 5, 2016. As of November, 2015, PHMSA had not received required data for analysis to ensure compliance with CFR Title 49, Subpart B, Part 193). Facility claimed a B5.7 Categorical Exclusion from NEPA review by the DOE in order to export LNG to non-FTA nations that went unchallenged by any federal agency.

2. New Fortress Energy, Titusville, FL

Titusville Logistics Center, 7600-7724 US-1, Titusville, FL 32780. Also known as American LNG Marketing, TICO Development Partners. DOE/FE ORDER NO. 3656 MAY 29, 2015, authorized LNG export to Free Trade Agreement countries, “up to 600,000 metric tons per annum, which American LNG states is equivalent to approximately 30.2 billion cubic feet per year (Bcf/yr) of natural gas (0.08 Bcf per day).” https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2015/08/f25/ord3656.pdf

But PHMSA denied approval on October 2, 2018, because of lack of a “Draft Environmental Assessment (DEA)” with “site drawings, maps, and other supporting documents.” https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/sites/phmsa.dot.gov/files/docs/standards-rulemaking/pipeline/special-permits-state-waivers/69596/2016-0073-tico-lod-denial.pdf

PHMSA still lists it as denied, “Last updated: Wednesday, October 17, 2018”. https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/pipeline/special-permits-state-waivers/phmsa-2016-0073

If constructed, this facility would be in violation of CFR Title 49, Subpart B, Part 193.2155(b). Citizens were forced to (1) obtain a legal opinion from PHMSA that the Federal Safety Regulation was, in fact, applicable, and (2) retain an attorney to ensure compliance.

3. Strom, Inc., Crystal River, Florida

6700 N Tallahassee Rd, Crystal River, FL 34428. This proposed LNG export “terminal” was approved by DOE for LNG export. Strom did file a Petition for Declaratory Order with FERC back in 2014 when it still planned to locate in Starke, Florida. FERC made no decision on the actual request; instead FERC responded: “ Because Strom has not submitted the filing fee within the required time, Strom’s petition for declaratory order is dismissed, and Docket No. CP14-121-000 is terminated.”

DOE has authorized Strom, Inc., to export 1,000,000 gallons of LNG/day. Strom has been telling FE every six months since 2016 that “Strom has reached a tentative agreement with the Port of Tampa in Tampa Florida, for long-term leases for shipping of LNG.” https://wwals.net/?p=55788 https://www.energy.gov/fe/articles/semi-annual-reports-strom-inc-fe-dkt-no-14-56-lng-order-no-3537

Yet on June 16, 2021, during a Port Tampa Bay Board meeting, the Port’s Principal Attorney, Charles E. Klug, said, “ I just want to clarify that Tampa Port Authority as a corporate entity doing business as Port Tampa Bay, does not have an agreement with Strom, and is not in negotiations with Strom, and does not plan to negotiate with Strom. Further, the port has no plans to export LNG through Port Tampa Bay, and any indication to the contrary is not correct.” https://wwals.net/?p=55794 https://zoom.us/rec/play/lI2IfkT1fOrPTbBmjQMb1FUFKr9oW8rY5KilWPER9Zn6eyszQCpVEe6D67t4d4nAJSHKo5sUOKFj1TU.F5g2FzlK7b-ggclD?continueMode=true

Following up on that Port Tampa Bay revelation, the Tampa Bay Times discovered that Strom had also failed to reach export agreements with other ports, that Duke Energy says its new electric power substation at Crystal River could not serve an LNG facility there, that Strom, Inc. does not own its proposed site in Crystal River and does not have an office at its stated office address, and that back in 2014 the Citrus County Board of County Commissioners (BOCC) declined to deal further with Strom after the BOCC discovered Strom had failed to pay that fee to FERC. [6] https://wwals.net/?p=56247

Strom LNG may finally be defunct. While Strom is usually up to a month or two late filing its semi-annual reports with DoE FE, it is now five months late filing its October 2021 report. [7]

While we are not known as cheerleaders for FERC, it nonetheless seems clear that if FERC had retained oversight of Strom, LNG, most of the above would not have happened and most likely Strom LNG would have been gone years ago.

4. Eagle Maxville LNG

16236 Normandy Blvd, Jacksonville, FL 32234. 16236 Normandy Blvd, Jacksonville, FL 32234. https://www.eaglelng.com/facilities/maxville-facility DOE/FE Order No. 4078, September 15, 2017, authorized Eagle Maxville to export 0.01 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d) of LNG, “to anywhere in the world not prohibited by U.S. law or policy. Eagle Maxville intends to export to markets in the Caribbean Basin and elsewhere in the region.” https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2017/09/f36/ord4078_0.pdf https://www.energy.gov/articles/us-department-energy-authorizes-eagle-maxville-small-scale-liquefied-natural-gas-exports

Operating since 2018. We do not locate a PHMSA Operator Identification Number. We do not know if this facility is in compliance with all of the Federal Safety Standards for LNG Facilities found in CFR Title 49, Subpart B, Part 193. In December 2020 Eagle Maxville LNG asked DoE/FE to extend its export permit term through 2050. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/12/07/2020-26780/eagle-lng-partners-jacksonville-ii-llc-application-to-amend-export-term-through-december-31-2050-for

This company has a FERC-jurisdictional sister company: Eagle LNG Partners Jacksonville, LLC.

5. JAX LNG of Pivotal LNG

9225 Dames Point Rd, Jacksonville, FL 32226. https://jaxlng.com/ JAX LNG was installed years later than the three Pivotal LNG liquefaction facilities in Georgia, and one each in Alabama and Tennessee. JAX LNG thus was not mentioned in the 2015 FERC Order regarding its Petition for Declaratory Order ( Pivotal ), because JAX LNG did not exist at that time. We can find no authorization for JAX LNG by FERC, FE, or MARAD; only a letter from the Coast Guard. Nonetheless, JAX LNG in May 2021 announced plans to triple its liquefaction capacity and double its LNG storage, both by 2022. https://www.jaxdailyrecord.com/article/jax-lng-tripling-liquefaction-capacity-at-dames-point-facility

D. Importance of methane as a greenhouse gas acknowledged by courts and FERC

Greenhouse gases, including methane from natural gas, have increasingly become recognized in legal precedents, starting with Sierra Club’s D.C. Circuit Court win against FERC and Sabal Trail in 2017, with co-plaintiffs Chattahoochee Riverkeeper and Flint Riverkeeper [8] “requiring the Commission to consider the reasonably foreseeable GHG emissions resulting from natural gas projects,” as FERC noted in its recent Interim GHG Policy Statement (see below). This Sierra Club precedent has been cited by the State of New York in denying a permit [9] for the Constitution Pipeline that resulted in that pipeline’s demise when FERC declined to overrule. [10] More recently, that Sierra Club case was cited by the D.C. Circuit Court [11] in revoking oil and gas leases in the Gulf of Mexico. [12]

The Commission itself in 2022 overhauled its pipeline approval process to emphasize greenhouse gases. [13] In FERC’s own statement [14] about this ruling: [15]

“The updates to the certificate policy statement include the first revision in more than 20 years to the Commission’s policy for the certification of new interstate natural gas projects under section 7 of the Natural Gas Act (NGA). With the interim GHG Policy statement, the Commission is taking a critical step in clarifying how it will address GHG emissions under the NGA and National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for proposed pipeline and LNG projects. The Commission is seeking comment on the Interim GHG Policy Statement.”

The Interim GHG Policy Statement implicitly raises the basic LNG issue that needs Rulemaking: [16]

22. Section 3(a) of the NGA provides for federal jurisdiction over the siting, construction, and operation of facilities used to import or export gas.

1

To date, the Commission has exercised section 3 authority to authorize: (1) LNG terminals located at the site of import or export and (2) the site and facilities at the place of import/export where a pipeline crosses an international border.

2

Additionally, NGA section 3(e) states that “[t]he Commission shall have the exclusive authority to approve or deny an application for the siting, construction, expansion, or operation of an LNG terminal.”

3

1 The 1977 Department of Energy Organization Act (42 U.S.C. 7151(b)) placed all section 3 jurisdiction under the Department of Energy. The Secretary of Energy subsequently delegated authority to the Commission to “[a]pprove or disapprove the construction and operation of particular facilities, the site at which such facilities shall be located, and with respect to natural gas that involves the construction of new domestic facilities, the place of entry for imports or exit for exports.” Department of Energy Delegation Order No. 00-004.00A, section 1.21A (May 16, 2006).

2 In addition to pipelines that cross the international border with Canada and Mexico, the Commission has also asserted authority over the portions of subsea pipelines planned to cross the “border” of the Exclusive Economic Zone between the U.S. and the Bahamas. See, e.g., Tractebel Calypso Pipeline, LLC, 106 FERC ¶ 61,273 (2004), vacated, Calypso U.S. Pipeline, LLC, 137 FERC ¶ 61,098 (2011).

3 15 U.S.C. 717b(e)(1).

FERC itself says it has “To date” it has only regulated LNG terminals at site of import or export or internaitonal borders, but in the next sentence it quotes NGA: “[t]he Commission shall have the exclusive authority to approve or deny an application for the siting, construction, expansion, or operation of an LNG terminal.” The NGA does not have the location restrictions FERC imposed upon itself in 2014 and 2015 with Shell, Emera, and Pivotal .

Without FERC environmental oversight, no-one knows how much risk inland LNG facilities and trucks and trains from them to export locations pose to nearby houses, schools, hospitals, and businesses. And no-one knows how much methane leaks from small inland LNG facilities, trucks, or trains contribute to the recently-discovered much greater methane emissions than previously known: [17]

Scientists have long struggled to pinpoint just how much methane is being released into the atmosphere. A series of earlier studies coordinated by EDF and hundreds of other researchers indicated that the U.S. oil and gas system leaked on average 2.3% of all the gas it produced. That’s about 60% more than the leakage rate reported by EPA, at 1.4%.

With U.S. LNG exports likely to ramp up as European countries stop buying Russian gas during the Ukraine war, environmental oversight is even more important for these inland LNG facilities that are the source of much exported LNG.

FERC should follow the actual law, as Commissioner Norman Bay wrote in his dissents to Shell, Emera, and Pivotal . It is time to rectify those mistaken decisions.

E. Method of reconsideration

In disclaiming jurisdiction over small-scale inland LNG export facilities, in former FERC Commissioner Norman Bay’s, (Past FERC Chairman), scathing Dissenting Opinion s to Shell, Emera, and Pivotal (see Attachments), Bay demonstrated how the interpretation of the Congressional intent, under the NGA, was neither reasonable nor permissible.

As in rulemaking, an agency is permitted to change its position on an issue so long as it explains the decision and the new interpretation is reasonable and permissible in light of the relevant statutory language.

Sarah McKinley of FERC’s Office of External Affairs informed WWALS on December 14, 2021, concerning a new 270,000-gallon LNG storage facility that has been proposed for construction within a designated “crash zone” area of the Homestead Air Reserve in Homestead, Florida:

To receive an official declaration of jurisdiction, you would have to file a motion for declaratory order, and the fee for that is over $20,000.

Neither the Commission nor any other individual or entity can require*** an entity to file a petition for declaratory order. However, if an individual believes there may be a violation of the Natural Gas Act, they can contact FERC’s enforcement hotline ( https://www.ferc.gov/enforcement-legal/enforcement/enforcement-hotline ) or file a formal complaint pursuant to the Commission’s regulations (18 CFR 385.206).

FERC can send an ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE, as it did in June 2020 to New Fortress Energy (NFE) about its Puerto Rico Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) facility: [18]

- In this order, pursuant to Rule 209(a)(2) of the Commission’s Rules of Practice and Procedure, 1 we direct New Fortress Energy LLC (New Fortress Energy) to show cause why the liquified natural gas (LNG) handling facility it has constructed adjacent to the San Juan Combined Cycle Power Plant at the Port of San Juan in Puerto Rico is not subject to the Commission’s jurisdiction under section 3 of the Natural Gas Act (NGA). 2

1 18 C.F.R. § 385.209(a)(2) (2019).

2 15 U.S.C. § 717b (2018).

And FERC did then decide, twice, that the NFE PR facility is FERC-jurisdictional. [19]

We are asking for FERC to formalize that same process in a Rulemaking. If FERC cannot require entities to file Petitions for Declaratory Order, nonetheless FERC can send ORDERs to SHOW CAUSE to each inland LNG facility. We would find that an adequate result of the rulemaking we request.

Regarding Ms. McKinley’s suggestion that we contact FERC’s contact hotline or file a formal complaint, we have no ability to compel any LNG facility to provide evidence. FERC does. We have provided evidence that FERC jurisdiction over inland LNG facilities is required by law, building on evidence previously provided by former FERC Commissioner Norman Bay and by FERC Chairman Richard Glick. We hope that in such a Rulemaking FERC will decide to reclaim its legally-required oversight.

IV. IDENTITY AND INTERESTS

-

WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc. (“WWALS”)

Since 2013, WWALS has opposed environmentally-damaging and unnecessary pipelines such as Sabal Trail and LNG operations such as by Pivotal LNG, by New Fortress Energy, and Strom LNG. In numerous filings with FERC WWALS has revealed environmental damages caused by Sabal Trail, from sinkholes and erosion to drilling leaks through the riverbed into the Withlacoochee River, as well as massive leaks from the then-future site of the Dunnellon Compressor Station. WWALS helped reveal that Strom, Inc. had been filing assertions with the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Fossil Energy that were contradicted by the other parties involved, such as the Port of Tampa, leading to the apparent demise of Strom’s planned Crystal River facility. Without FERC oversight, little is known about the environmental effects of small inland LNG facilities. WWALS has members in both Georgia (where Pivotal LNG has three LNG operations) and Florida (where Pivotal has another LNG operation, plus many more by other organizations). LNG trucks and rail cars go by schools, businesses, homes, and churches attended by our members. WWALS members, collectively and individually, have a substantial interest in ensuring that lack of oversight by FERC does not lead to more risk to human life, the environment, and climate. WWALS thus has a substantial interest in the instant request for rulemaking and any processes arising therefrom.

WWALS contributed to the lawsuit Sierra Club won against FERC and Sabal Trail, which has been cited by New York State in denying a permit that caused the demise of the Constitution Pipeline, by the U.S. Sixth District Court in vacating oil and gas leases in the Gulf of Mexico, and by FERC itself in its new Greenhouse Gas Guidelines. Recent research has revealed far more methane leaks than had previously been known. See III. D. Importance of methane as a greenhouse gas acknowledged by courts and FERC . In the light of this renewed attention to greenhouse gases, it is time for FERC to take back up its oversight of small inland LNG operations.

-

LEAD Agency, Inc. (“LEAD”)

Oklahoma is a large source for this natural gas and we are tired of the earthquakes that have ruined and damaged our homes as a result of fracking for the gas and oil in our state. It has not only ruined hundreds of homes, including destroying Earl Hatley’s (Grand Riverkeeper) and damaging Rebecca Jim's (Tar Creekkeeper), it has and will continue to cause ground and surface water contamination in the state. Thus LEAD Agency, Inc., the parent organization of Grand Riverkeeper and Tar Creekkeeper, support this petition to hold FERC accountable for these facilities and ultimately our climate.

LEAD members, collectively and individually, have a substantial interest in ensuring that lack of oversight by FERC does not lead to more risk to human life, the environment, and climate. LEAD thus has a substantial interest in the instant request for rulemaking and any processes arising therefrom.

-

Kissimmee Waterkeeper (“Kissimmee”)

In the flatlands of Florida, the state most already and soon even more affected by climate change, Kissimmee Waterkeeper and its members have a direct interest in preventing the greenhouse gases released by LNG operations with no FERC oversight, as well as in the more immediate risks from LNG trucks and trains passing nearby.ividually, have a substantial interest in ensuring that lack of oversight by FERC does not lead to more risk to human life, the environment, and climate. Kissimmee thus has a substantial interest in the instant request for rulemaking and any processes arising therefrom.

-

Our Santa Fe River (“OSFR”)

Our Santa Fe River was a founding member of "Floridians Against Fracking" and planned, traveled to and stood in Legislative committee hearings in Tallahassee for many long years. We fought four years to stop the permitting and construction of Sabal Trail Gas Transmission pipeline and we have opposed oil and gas pipelines, fracking and LNG transport in Georgia and especially throughout the State of Florida. Sabal Trail has put a dangerous pipeline through a fragile, sinkhole-infested area on the borders of the Suwannee River against the warnings of disinterested geologists, and put their pipe under the Santa Fe River where it remains a constant threat to our river and aquifer. OSFR opposes all types of non-sustainable energy which pose threats to our water, air and earth as well as the inhabitants of Florida. OSFR thus has a substantial interest in the instant request for rulemaking and any processes arising therefrom.

-

Center for a Sustainable Coast

Since being established in 1997, the Center has given priority to water protection and, more recently, climate change caused by the release of greenhouse gasses. Scientific studies have determined that even a small percentage of leaked natural gas will cause unacceptable increases in the heat-trapping effects of GHGs, and therefore the cumulative consequences of extracting, processing, and distributing natural gas are dire. The board and members of the Center seek to ensure that FERC’s responsibilities provide consistently reliable and verifiable accountability to prevent such emission risks at all gas facilities regulated by the agency.

-

Three Rivers Waterkeeper

Three Rivers Waterkeeper (3RWK) was founded in 2009 and aims to improve and protect the water quality of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers through scientific and legal advocacy. These waterways are critical to the health, vitality, and economic prosperity of our region and communities. We work to ensure our three rivers are protected and safe to drink, fish, swim and enjoy, but the unconventional oil and gas industries threaten that vision. LNG can often be acquired through fracking with the use of injection wells that pose many threats to our public and environmental health. The fluids that are used in oil and gas extraction contain toxic metals and radioactive chemicals. Radium-226 and Radium-228, chemicals found in fracking waste, are known carcinogens and can cause bone, liver, and breast cancer at high concentrations. Once fluids are injected into geologic formations, it is difficult to track where these fluids can migrate. Injection wells are designed to inject in layers of permeable rock that are capped by impermeable rock, however fluid can move laterally. When this happens, toxic fluid can seep into cracks from other wells or cracks in rock layers. Injected fluids can also migrate up abandoned wells under pressure. In many of the older unregulated abandoned wells, cracks in well casings can allow toxic fluids to seep into different layers. Furthermore, this is compounded when LNG and its extraction wastes are transported and exported with little regulated oversight. This lets toxic fluid seep into places it shouldn't be. Leaking injection wells and transport systems can contaminate aquifers, rivers, and lakes with radioactive toxins, endangering communities’ drinking water supplies and posing serious threats to human health.

Three Rivers Waterkeeper have a substantial interest in ensuring that lack of oversight by FERC does not lead to more risk to human life, the environment, and climate, and thus request for timely rulemaking and any processes arising therefrom.

- Lumber Riverkeeper, Winyah Rivers Alliance

The effects of climate change are already evident in the waterways of the Nationally designated Wild and Scenic Lumber River, located in southeastern North Carolina and northeastern South Carolina. Along with erratic shifts in flooding and droughts and an increase in overall temperature in the region, the Lumber River watershed went through two 1000 year flood events due to enormous amounts of rainfall from Hurricanes Matthew in 2016 and Florence in 2018. With the planned Atlantic Coast Pipeline canceled, Piedmont Natural Gas, a wholly owned subsidiary of Duke Energy, constructed the Robeson LNG liquefaction facility (Robeson LNG) and four-mile supply pipeline without any FERC oversight and minimal state oversight. Built in Wakulla, Robeson County, NC, the facility is located in a high poverty area with a population that is 85% American Indian. With associated pipelines to funnel gas back and forth to the plant, Robeson LNG is impacting wetlands that are crucial to preventing future flooding in the Lumber River Watershed. Further this inland LNG, with its ability to clean, store and transfer gas by truck, creates harmful impacts from leaks of methane, other gasses and filtered pollutants into the watershed and atmosphere. This pollution stream has negative effects on the health and life of our streams, climate and the communities that call this area home. Lumber Riverkeeper has a substantial interest in ensuring that lack of oversight by FERC does not lead to more risk to human life, the environment, and climate, and thus request for timely rulemaking and any processes arising therefrom.

V. REQUEST FOR RULEMAKING

A. What FERC’s Strategic Plan and the NGA say FERC should do

From the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission – Strategic Plan FY 2014–2018 March 2014 :

- Conduct comprehensive and timely safety inspections of hydroelectric and LNG facilities. Failure of an LNG facility or a non-federal hydropower project can result in loss of life and significant environmental and economic consequences .

- To fulfill its responsibility for ensuring the safety of these facilities, FERC relies on physical inspections for detecting and preventing potential catastrophic structural failures, thereby protecting the public against the risk associated with such an event.

- FERC engineers are highly trained and work closely with local officials at all stages of project development and operation.

- Before projects are constructed, the designs, plans, and specifications of the proposed facility are reviewed and approved.

- Through regularly scheduled and comprehensive inspections during construction and operation, FERC engineers verify that dams and LNG facilities meet stipulated design criteria, identify necessary remedial modifications or required maintenance, and ensure compliance with requirements.

- The Commission ensures the safety of the public, as well as the continued operation of the facilities to meet the energy demands of the nation.

- In accordance with NEPA, highly-trained FERC staff thoroughly analyze environmental effects of proposed LNG facilities and coordinate with other agencies to consider environmental statutes, including Coastal Zone Management Act and Clean Water Act. LNG “Terminals” encompass more than just “Marine-Based” LNG export facilities.

15 U.S. Code § 717a (11) : “ LNG terminal ” includes all natural gas facilities located onshore or in State waters that are used to:

- Receive, unload, load, store, transport, gasify, liquefy; or

- Process natural gas importe d to United States from foreign country, or exported to foreign country from the United States, or transported in interstate commerce by waterborne vessel

Does not include :

- Waterborne vessels used to deliver natural gas to or from any such facility; or

- Any pipeline or storage facility subject to jurisdiction of the Commission under Section 717f

15 U.S. Code § 717f – Construction, extension, or abandonment of facilities

- After notice and opportunity for hearing, if FERC finds such action necessary or desirable in the public interest, Commission may by order direct a natural-gas company to extend or improve its transportation facilities;

- To establish physical connection of its transportation facilities with the facilities of, and sell natural gas to, any person or municipality engaged or legally authorized to engage in the local distribution of natural or artificial gas to the public; and

- Extend its transportation facilities to communities immediately adjacent to such facilities or to territory served by such natural gas company.

B. Time to reconsider and revisit

As Chairman Glick wrote in his Concurring Opinion in New Fortress Energy LLC, ORDER ON SHOW CAUSE, 174 FERC ¶ 61,207 (March 19, 2021). Docket No. CP20-466-000 :

1. We concur in today’s order finding New Fortress Energy LLC's liquefied natural gas (LNG) facility subject to the Commission’s jurisdiction under section 3 of the Natural Gas Act (NGA). We write separately to explain our view that it is time to reconsider our precedent in Shell U.S. Gas & Power, LLC (Shell), which held that a facility must be connected to a pipeline to be a jurisdictional LNG terminal. 1 ….

3. Nowhere does the statute say that a facility must be connected to a pipeline to qualify as an LNG terminal and, thus, come within the Commission’s jurisdiction under section 3. 4 We should revisit Shell to ensure that we are carrying out our statutory responsibilities under the letter of the law. "

1 Shell U.S. Gas & Power, LLC, 148 FERC ¶ 61,163, P 43 (2014).

4 See Lomax v. Ortiz‐Marquez, 140 S. Ct. 1721, 1725 (2020) (“[T]his Court may not narrow a provision’s reach by inserting words Congress chose to omit.”): Virginia Uranium, Inc. v. Warren, 139 S. Ct. 1894, 1900 (2019) (plurality opinion) (The Court’s “duty [is] to respect not only what Congress wrote but, as importantly, what it didn’t write.”).

C. Summary: safety, environmental, and economic consequences

For the wide-ranging environmental and safety consequences of FERC’s abdication of oversight of inland LNG facilities, see Section III.B and C.

Developers are taking advantage of the loophole FERC created in disclaiming jurisdiction over small-scale inland LNG export facilities. Such facilities are thus lacking FERC’s environmental, construction, and safety oversight, causing risk of “ loss of life and significant environmental and economic consequences,” according to FERC’s own strategic plan (see Section VI.A).

Some of the economic consequences of FERC’s tilting of the playing field were expressed by Floridian Natural Gas Storage (FGS) on June 12, 2015, as Accession Number: 20150612-5136 in Docket No. CP13-541:

“During its pendency, the Commission has determined that certain LNG projects are outside its jurisdiction, permitting those projects to compete free from the FERC regulatory burdens that FGS and other FERC-regulated projects bear in what has become an active, urgent and highly competitive small-scale LNG market."

What FGS views as regulatory burdens we view as public goods of construction, environmental, and safety review, but the FGS point remains that competition has been warped by FERC’s inland LNG export decisions.

VI. PROPOSED RULE

Petitioners respectfully request that the Commission issue a formal Rulemaking to revisit, consider, and modify the Commission’s former decisions about inland LNG export facilities, including Shell, Emera, and Pivotal.

We propose three options for the result of such Rulemaking:

A. Revoke previous decisions and take back up oversight of inland LNG export facilities; or

FERC should revoke its Shell, Emera, and Pivotal decisions, thus requiring all LNG export facilities to be under FERC oversight, as the NGA requires, thus closing the significant and unnecessary gap FERC created in its own jurisdiction.

B. Mandate Petitions for Declaratory Order; or

If FERC is not willing to revoke its Shell, Emera, and Pivotal decisions , it should m andate developers of proposed small-scale inland Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) export facilities file Petitions for Declaratory Order with the Commission in order for FERC to determine federal jurisdiction before a developer proceeds with a project, thereby affording FERC an opportunity to:

- Review the proposal;

- Fully understand what the project entails, including ultimate destination and end-users of the LNG;

- Ask pertinent questions; and

- Establish a formal Docket for a proposed project in order for the public to fully participate in the approval process.

C. Send ORDERS to SHOW CAUSE to each inland LNG export facility

If FERC cannot mandate such Petitions for Declaratory Order, nonetheless FERC can and should send ORDERs to SHOW CAUSE to each inland LNG facility that FERC does not currently consider FERC-jurisdictional.

VII. CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the Commission should issue a NOPR to revisit, reconsider, and ideally revoke its previous decisions against oversight of inland LNG facilities , in order to address the economic, environmental, and safety problems caused by those previous decisions, thus closing the significant and unnecessary gap FERC created in its own jurisdiction .

Respectfully submitted,

John S. Quarterman, Suwannee RIVERKEEPER®

/s

WWALS Watershed Coalition, Inc.

Earl L. Hatley, President

/s

LEAD Agency, Inc. (Grand Riverkeeper®, Tar Creekkeeper®)

John C. Capece, Ph.D., Executive Director and Waterkeeper

/s

Kissimmee Waterkeeper®

Terry Phelan, Interim President

/s

Our Santa Fe River, Inc.

David Kyler, Director

/s

Center for a Sustainable Coast

Heather Hulton VanTassel, Executive Director

/s

Three Rivers WATERKEEPER®

Jefferson Currie II, Lumber Riverkeeper®

/s

Winyah Rivers Alliance

July 19, 2022

ATTACHMENTS

Shell: Norman Bay Dissent, 148 FERC ¶ 61,163 (Sept. 4, 2014), Docket No. RP14-52-000

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION

|

Emera CNG, Inc. |

Docket No. |

CP14-114-000 |

(Issued September 4, 2014)

BAY, Commissioner, concurring in part and dissenting in part:

I concur with the majority’s determination that Shell U.S. Gas & Power LLC’s proposed activities do not fall within the jurisdictional exemption created by section 1(d) of the Natural Gas Act. I disagree with the majority’s conclusion regarding the scope of the Commission’s jurisdiction under section 3 of the Act.

The Energy Policy Act of 2005 “explicitly provides the Commission with exclusive authority over LNG terminals subject to our section 3 jurisdiction.” The Gas Company, 142 FERC ¶ 61,036, P 17 (2013). The majority acknowledges that, in doing so, Congress employed “a very broad definition of ‘LNG Terminal’” (Order P 43); namely, “ all natural gas facilities located onshore or in State waters that are used to receive, unload, load, store, transport, gasify, liquefy, or process natural gas” that is imported to, or exported from, the United States, or “transported in interstate commerce by waterborne vessel.” 15 U.S.C. § 717a(11) (emphasis added).

It is beyond dispute that Shell’s proposed Canadian project will involve facilities that will “receive,” “unload” and “store” “natural gas that is imported [from Canada] to the United States.” Similarly, the proposed Geismar project would “receive” and “liquefy” natural gas and then load it on to “waterborne vessels” for “transport in interstate commerce.” See Order PP 4-5. Nonetheless, the majority finds that neither involves an “LNG terminal” within the meaning of section 2(11) of the Natural Gas Act, 15 U.S.C. § 717a(11). That conclusion cannot be squared with the plain language of the Act.

The majority’s determination is based, in part, on the fact that the Commission has generally limited its jurisdiction under section 7 of the Natural Gas Act to facilities that send or receive natural gas by pipeline. See Order P 43. But section 7 speaks of the Commission’s jurisdiction over “transportation facilities.” See 15 U.S.C. § 717f(a). Section 2(11) defines “LNG terminals” to include “all natural gas facilities,” not merely natural gas “transportation facilities.” See 15 U.S.C. § 717a(11) (“‘LNG terminal’ includes all natural gas facilities … that are used to receive, unload, load, store, [or] transport … natural gas”). The former is clearly broader than the latter, and had Congress intended a more limited approach it could have used the language of section 7 in section 3. The majority also argues that, although the projects – in particular, the Geismar project – will involve natural gas “transported in interstate commerce by waterborne vessel,” the only waterborne transportation that counts for purposes of section 2(11) is interstate delivery to a facility that is connected to a pipeline (whether intrastate or interstate). See Order PP 43, 48. In support, the majority points to a jurisdictional dispute between California and FERC involving this fact pattern that preceded the enactment of the Energy Policy Act of 2005. Id. If anything, that history suggests that Congress intended to pre-empt state action and used broad language to accomplish that result, providing “exclusive authority” to FERC with respect to LNG terminals, 15 U.S.C. § 717b(e)(1), including “all natural gas facilities” in which natural gas was “transported in interstate commerce by waterborne vessel,” id. § 717a(11).

While one might debate the relative policy arguments for or against a finding of FERC jurisdiction, we are constrained, as we should be, by the language of the statute. Here, I believe the plain meaning of the statute compels a different result. Accordingly, I must respectfully dissent.

______________________

Norman C. Bay

Commissioner

Emera: Norman Bay Dissent, 148 FERC ¶ 61,219 (Sept. 19, 2014), Docket No. CP14-114-000

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION

|

Emera CNG, Inc. |

Docket No. |

CP14-114-000 |

(Issued September 19, 2014)

BAY, Commissioner, dissenting :

In enacting the Natural Gas Act, Congress emphasized the importance of regulating the sale of gas in foreign commerce. In section 1(a), Congress declared that “Federal regulation in matters relating to the transportation of natural gas and the sale thereof in interstate and foreign commerce is necessary in the public interest.” 15 U.S.C. § 717(a). In section 1(b), Congress stated that the provisions of the Act “shall” apply to “the importation or exportation of natural gas in foreign commerce and to persons engaged in such importation or exportation.” Id . § 717(b). If there were any lingering doubt over congressional intent, section 3 removes it when the Act refers to foreign commerce a third time: “[N]o person shall export any natural gas from the United States to a foreign country or import any natural gas from a foreign country without first having secured an order of the Commission authorizing it to do so.” Id . § 717b(a). As a result, the Commission exercises authority over the siting, construction, operation, and maintenance of export facilities in order to ensure that any authorized exports will serve the public interest. See, e.g., NET Mex. Pipeline Partners , LLC , 145 FERC ¶ 61,112, P 13 (2013).

Here, Emera’s facilities fall within the four corners of the statute. They are facilities involving natural gas intended for export to a foreign country. As the majority acknowledges, “the stated purpose of Emera’s CNG facility will be to compress gas so that it can be exported in ISO containers” to the Commonwealth of the Bahamas. Order P 10. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Emera has applied to the Department of Energy– under section 3 of the Natural Gas Act – “for long-term authorization to export CNG from” its proposed facility, and properly so. See 79 Fed. Reg. 38,017, 38,018 (July 3, 2014). Yet, in the majority’s view, that very same facility is not an “export facility” under section 3.

Of course, this raises the question of how what would plainly appear to be a gas export facility is not, in fact, an export facility. The majority’s argument seems to be that because the CNG will leave Emera’s facility by truck and travel a quarter of mile before being loaded onto ocean-going carriers for export – rather than by a pipeline running across a border or to a tanker – the facility is not an “export facility” under section 3 of the Natural Gas Act. Id . P 13. It cannot be that the Commission’s jurisdiction turns on this 440-yard truck journey.

The majority suggests that the scope of the Commission’s jurisdiction under section 3 must be consistent with section 7 of the Natural Gas Act. Jurisdictional export facilities – other than “LNG terminals” – thus must have the defining characteristic of interstate transportation facilities, namely a send-out pipeline. Order P 13. But conflating section 3 with section 7 is not supported by the language of the statute. Section 7 speaks of natural gas “transportation facilities,” 15 U.S.C. § 717f; section 3 does not, id . § 717b. And none of the language which led the Commission to conclude that section 7 is limited to transportation by pipelines is present in section 3 (nor any of the related delegation and executive orders). See, e.g., Exemption of Certain Transp. and/or Sales of LNG from the Requirements of Section 7(c) of the NGA , 49 F.P.C. 1078, 1079-80 (1973) (discussing Commission’s section 7 jurisdiction). Moreover, section 1(b) demonstrates the breadth of the Act by making a distinction between interstate transportation or sales on the one hand, and importation and exportation on the other, all of which are covered. See 15 U.S.C. § 717(b) (applying the Act to “natural gas companies engaged in such transportation or sale, and to the importation or exportation of natural gas in foreign commerce and to persons engaged in such importation or exportation”) (emphasis added).

The result reached by the majority also suggests that, if the boundaries of a facility do not encompass the actual point of export, it cannot be an “export facility” under section 3. But the Department of Energy Delegation Order providing the Commission with authority over export facilities differentiates between the place of export and the facilities necessary to implement that export, and gives no indication that the former must be located within the latter. See DOE Delegation Order No. 00-004.00A, at ¶ 1.21.A (delegating to FERC, with respect to “the imports and exports of natural gas,” the authority to “[a]pprove or disapprove the construction and operation of particular facilities, the site at which such facilities shall be located, and with respect to natural gas that involves the construction of new domestic facilities, the place of entry for imports or exit for exports”).

As a policy matter, one could certainly debate the merits of whether or not FERC should assert jurisdiction over Emera’s export facility. But where Congress has spoken there is no room for such a debate. Here, Congress’s intent is clear: federal regulation over the sale of gas in foreign commerce “is necessary in the public interest.” 15 U.S.C. § 717(a).

That Congress might require federal oversight of foreign commerce should not be a surprise. See, e.g ., Michelin Tire Corp. v. Wages , 423 U.S. 276, 285 (1976) (“the Federal Government must speak with one voice when regulating commercial relations with foreign governments”). The Commission itself has previously recognized that “[t]he nation’s energy needs are best served by a uniform national policy” applicable to the export or import of natural gas in foreign commerce. Sound Energy Solutions , 106 FERC ¶ 61,279, P 27 (2004). The Commission’s ability to implement any such national policy may now be subject to the vagaries of where an exporter chooses to put the fence around its facility or by the trucking of gas a short distance to the docks.

In my view, regardless of the manner in which the CNG leaves Emera’s plant, the facility should be called what it is: a natural gas export facility. Accordingly, I respectfully dissent from the determination that Emera’s facilities are not subject to the Commission’s jurisdiction under section 3 of the Natural Gas Act.

______________________

Norman C. Bay

Commissioner

Pivotal: Norman Bay Dissent, 151 FERC ¶ 61,006 (Apr. 2, 2015), Docket No. RP15-259-000

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

FEDERAL ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION

|

Pivotal LNG, Inc. |

Docket No. |

RP15-259-000 |

(Issued April 2, 2015)

BAY, Commissioner, dissenting :

One might well wonder how a natural gas facility that is used to export gas and that must obtain an export license from the Department of Energy is not, from FERC’s perspective, an “export” facility within the meaning of the Natural Gas Act and thus not subject to FERC’s jurisdiction. If this inconsistency seems puzzling, that’s because it is. Logic, not to mention the plain language of the Act, compels a different result. Nevertheless, in Emera CNG, LLC , 1 over my dissent, the Commission held that a natural gas facility used to export gas to the Bahamas was not an “export” facility because the gas from the facility had to be trucked 440 yards to the docks. Relying on the reasoning of Emera , Pivotal, which operates five LNG facilities in three different states, seeks a similar declaratory order. For the reasons I stated in Emera , I would deny Pivotal’s request as well.

The central flaw in the majority’s reasoning is that it fails to address the plain language of the Natural Gas Act. The Act makes clear Congress’s intent to regulate the import and export of gas. Section 1(a) declares that “[f]ederal regulation” of the “transportation of natural gas and the sale thereof in interstate and foreign commerce is necessary in the public interest.” 2 Section 1(b) similarly provides that the Act “shall” apply to “the importation or exportation of natural gas in foreign commerce and to persons engaged in such importation or exportation.” 3 To that end, section 3 states that “no person shall export any natural gas from the United States to a foreign country or import any natural gas from a foreign country without first having secured an order of the Commission authorizing it to do so .” 4 To effectuate these congressional directives, the Department of Energy authorizes the export of the commodity natural gas, while the Commission exercises authority over the siting, construction, operation, and maintenance of export facilities in order to ensure that any authorized exports will serve the public interest. 5

Here, the majority acknowledges that “liquefaction facilities operated by Pivotal and its affiliate … [will] produce liquefied natural gas that [will] ultimately be exported to foreign nations by a third party” and that such foreign sales must be made pursuant to an export license from DOE. 6 There can be little doubt, therefore, that the facilities will be involved in the “exportation of natural gas in foreign commerce.” 7

Instead of addressing the plain language of the statute, the majority simply ignores it – not once is section 1(a) or (b) or section 3(a) even acknowledged – and proceeds to create its own exemption by misreading and conflating section 3(e) and section 7 of the Act. Section 3(e) relates to “LNG terminals;” section 7 covers “transportation facilities.” First, the majority observes that Pivotal’s facilities are located inland and incapable of transferring LNG directly to tankers. 8 These facts establish that the facilities do not constitute an “LNG terminal” as defined by section 2(11) of the Act. 9 But the Commission’s jurisdiction under section 3 extends to export facilities, not merely “LNG terminals.” The two are not the same. Under section 2(11), “LNG terminal” is defined to include facilities used for import, export, or interstate commerce. An LNG terminal is simply one type of export facility. Indeed, the first commercial LNG facility was not built until 1941, three years after enactment of the Natural Gas Act. 10 The first U.S. export terminal was completed in 1969. 11 There is no evidence to suggest that Congress sought to limit export facilities to “coastal LNG terminals that are accessible to ocean-going, bulk-carrier LNG tankers and that are connected to pipelines that deliver gas to or take gas away from the terminal.” 12

Second, the majority notes that LNG “would be transported, by means other than interstate pipeline, to the ultimate point of export.” 13 But nothing in section 3 conditions the Commission’s jurisdiction upon the existence of a pipeline running to the point of export. The majority’s view that a pipeline is a condition to jurisdiction stems from an inappropriate attempt to graft concepts developed under section 7 of the Act, which addresses the Commission’s jurisdiction over interstate “transportation facilities,” to section 3, which governs the exportation of natural gas. 14 Congress has made clear that there is a distinction between domestic transportation or sales – which are only jurisdictional if they are interstate in character –and foreign imports or exports, all of which are covered. 15 And the DOE Delegation Order, which provides the Commission with authority over export facilities, is equally bereft of language that would support the majority’s view that jurisdictional export facilities must share the defining characteristics of interstate transportation facilities. 16

The majority attempts to buttress its analysis with the claim that an “over-expansive application of section 3” is unnecessary here because Pivotal’s “facilities are regulated by various federal, state and local agencies.” 17 Of course, the same is true with respect to the “traditional” LNG terminals and cross-border pipelines that the majority concedes are subject to the Commission’s jurisdiction. More important, the Commission may not substitute its policies for those enacted by Congress. Section 3 is clear: “no person shall export any natural gas from the United States to a foreign country or import any natural gas from a foreign country without first having secured an order of the Commission authorizing it to do so.” 18

There are sound policy reasons in support of section 3’s broad language, not the least of which is national uniformity. Under the majority’s construct, gas export facilities will be subject to a patchwork of potentially conflicting state regulatory requirements. That result is contrary to the Commission’s long-held view that “[t]he nation’s energy needs are best served by a uniform national policy” with respect to gas in foreign commerce. 19 The majority has also foreclosed the opportunity for some developers to affirmatively seek the benefit of federal jurisdiction, including FERC’s siting authority and established regulatory framework. Residents of a state in which the facility is located, or residents of surrounding states, may reasonably expect the facility to be subject to federal review of its operations and maintenance. While some states may have the staff and expertise to do this, others may not.

Unfortunately, the majority today ignores the plain language of the statute, substitutes its policy judgment for that of Congress, and undermines national uniformity with respect to the import or export of gas. While one might debate the relative policy arguments for or against a finding of non-jurisdiction, such a debate is not for us when Congress has spoken. It is not for us to call a congressional directive “over expansive.” While it is difficult to know what the unintended consequences of today’s order will be, one consequence is not: the Commission creates a significant and unnecessary gap in FERC’s jurisdiction.

For all those reasons, I respectfully dissent.

______________________

Norman C. Bay

Commissioner

1 148 FERC ¶ 61,219 (2014).

2 15 U.S.C. § 717(a).

3 Id . § 717(b).

4 Id . § 717b(a) (emphasis added).

5 See, e.g., NET Mex. Pipeline Partners , LLC , 145 FERC ¶ 61,112, P 13 (2013).

6 See Order PP 1, 13.

7 15 U.S.C. § 717(b).

8 See Order P 12.

9 See Pivotal LNG , 148 FERC P 61,164 (Bay, Comm’r, concurring).

10 See Henry F. Lippitt, Regulatory Problems in the Development and Use of Liquid Methane , 39 Tex. L. Rev. 601, 603 (1961).

11 See Conocophillips Alaska Natural Gas Corp. & Marathon Oil Co ., 126 FERC ¶ 61037, P 3 (2009).

12 Order P 8.

13 Id . P 12.

14 See, e.g ., Shell U.S. Gas & Power , 148 FERC ¶ 61,163 (2014) (Bay, Comm’r, dissenting).

15 See 15 U.S.C. § 717(b) (applying the Act to “natural gas companies engaged in [interstate] transportation or sale, and to the importation or exportation of natural gas in foreign commerce and to persons engaged in such importation or exportation”) (emphasis added).

16 See DOE Delegation Order No. 00-004.00A, at ¶ 1.21.A (delegating to FERC, with respect to “the imports and exports of natural gas,” the authority to “[a]pprove or disapprove the construction and operation of particular facilities, the site at which such facilities shall be located, and with respect to natural gas that involves the construction of new domestic facilities, the place of entry for imports or exit for exports”).

17 Order P 13.

18 15 U.S.C. § 717b(a).

19 Sound Energy Solutions , 106 FERC ¶ 61,279, P 27 (2004).

wwalswatershed@gmail.com PO Box 88, Hahira, GA 31632 Page of 850-290-2350 www.wwals.net

[1] Shell U.S. Gas & Power, LLC (“ Shell ”), 148 FERC ¶ 61,163 (Sept. 4, 2014) , Docket No. RP14-52-000,

Emera CNG, LLC (“Emera”), 148 FERC ¶ 61,219 (Sept. 19, 2014) , Docket No. CP14-114-000,

Pivotal LNG, Inc. (“Pivotal” or “Pivotal II”), 151 FERC ¶ 61,006 (Apr. 2, 2015), Docket No. RP15-259-000

[2] APA; 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A).

[3] PHMSA, December 5, 2019, GRANTEE: Energy Transport Solutions, LLC, Doral, FL, DOT-SP 20534 https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/sites/phmsa.dot.gov/files/docs/safe-transportation-energy-products/72906/dot-20534.pdf